Portraits de situations

Casualness

Since 1994, Paul Pouvreau's world - or, more precisely, the diegetic universe he establishes through his photographs - has unfolded in spaces of varying nature and scale, sometimes so small that all you can make out is the end of a table, part of a wall, a few trees along a path, and so on. The scenes take place in factory or workshop corners, soberly furnished domestic spaces, fragments of urban spaces, sometimes more characterized landscapes chosen, it seems, for the curious aspect they present once photographed. This world, in which man appears only episodically, is populated for the most part by objects and materials associated with the flow of goods: cardboard boxes, plastic bags, newspaper or magazine pages and other packaging materials, most of which display on their surface, crudely printed, drawings, pictograms, photographs, logos, instructions for use or advertising mentions. Often, the layout of the staging, and even the presence and gestures of human beings, seem subordinate to the visibility, or rather, the legibility, of these graphic forms. In Le Navigator (1999), for example, the bus shelter, like a shop window, appears as a display structure adapted to the logo inscribed on the card carried by the man. In fact, the construction of Paul Pouvreau's photographs often plays on these two modes of merchandise display: the shop window and the display case. The viewer is invited to scrutinize mimetic forms and inscriptions that he or she would willingly call insignificant - in every sense of the word, since their relationship in the images often invites the viewer to improvise a kind of hermeneutic, which certain works, such as Le Fossé (1998) or Eve (2003), render quite complex. This attention to insignificant representations recalls Raymond Roussel and his strange exercises in description-narration of a mineral water bottle label, hotel stationery or a hatter's advertising card. In these poems, as in Paul Pouvreau's scenes, the hierarchy of expository values is dissolved. It cracks under the impact of the excessive distortion between the poverty of the object and the investment of the attention paid to it. It cracks under the impact of the excessive distortion between the poverty of the object and the investment of attention it receives. The value of the merchandise itself is laid bare by its packaging; this is how we might describe this operation, following the artist's own hijacked homage to Marcel Duchamp in Le Porte-bouteille (1998). A photograph in which, literally, the hold of things over man appears as a consequence of the crisis of exhibition value. Indeed, the ready-made was one of the first critical expressions of this crisis in the field of art.

Read more

Between the exposure of value and the envelope of merchandise lies one of the essential gestures - the very aesthetic - of Paul Pouvreau's work, that of désinvolture. Indeed, the etymology of the term désinvolture (formed from the Italian involto, “wrapped”, “wrapped up”) describes precisely the extraction of an object from its envelope, which meaning can be extended in the figurative sense of a refusal to get caught up in a game, to undo the self-evident character of a situation, a thing, a system, such as that of value, here, in Pouvreau's work. Hence this highly effective tension between the absence of value in the packaging materials and the extrinsic value of the large, colorful, advertising-finish prints that showcase them.

Moreover, casualness, in its common sense, is one of the defining characteristics of the ignorant. It is because he is intrinsically disposed to this unusual way of being free in his attitudes, in his movements, free, of a freedom in the face of technique, customs and the laws of the trade, that the model so easily crosses the boundary of representation to reveal, in fine, the device, the cogs, in short, both the physical and mental machinery. Such casualness acts as a diffuse mood throughout Paul Pouvreau's work. Occasionally, however, one thinks one discerns it in the man who, in turn, bivouacs in front of a poster landscape, La Légende (1996), lies sprawled under a table in the middle of a kitchen overrun with utensils , Sans titre (1999), or stretches a strip of wallpaper in front of a brick wall. A gesture emblematic of L'Entreprise (1997), which stages and includes the viewer's situation in a way that remains to be clarified. While this gesture derisively reduces the viewer's gaze to evaluating the fit of a set element, it also initiates the shift from theatricality to exhibition space that the artist has been implementing since 1999, as if he were replaying, in more complex terms, the experience of the installation Transfert (1980).

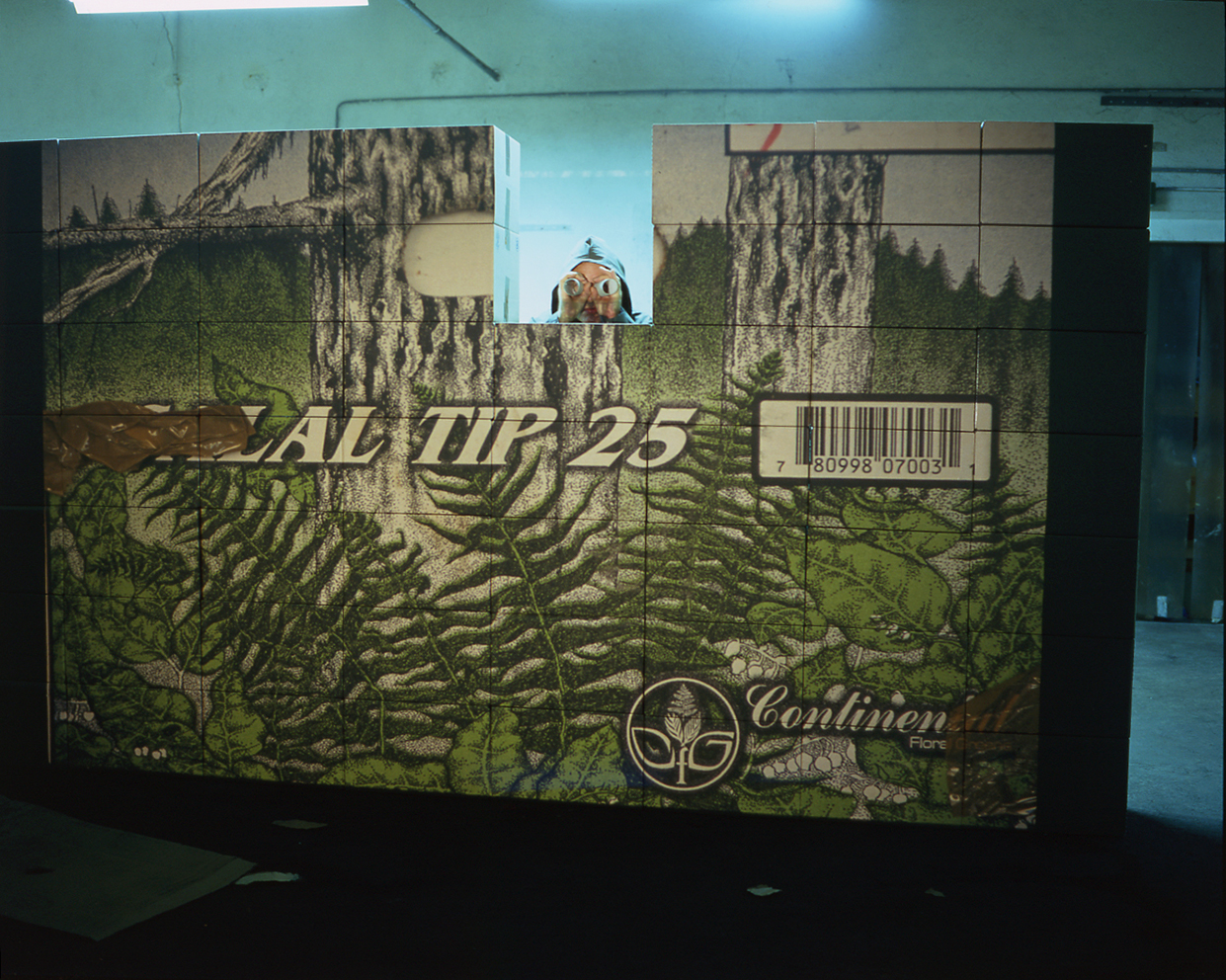

In fact, since that date, cardboard architectures - fresh out of the factory and untouched by any inscriptions whatsoever - appear both in certain photographs and in the middle of the exhibition space, close to the prints, some of which are sometimes embedded in the surface of these constructions. The viewer thus finds himself in the midst of a reciprocal contamination of the inside and outside of the image, which is hardly an invitation to cross the mirror. Considering the ambiguity between work and exhibition view that characterizes photographs such as Le Bureau (1999) and La Façade (2000), this situation invites us to reassess the status of images in relation to the notion of work, which is ultimately unstable here. All the more so as the cardboard structures only exist for the time of their exhibition. Absent from the catalog of the artist's works, they have the singular function of prolonging the photographs, as if they were, in a way, exhibition prostheses. But these prostheses have an ambivalent function, to say the least, since they make visible as much as they conceal, and contribute effectively to undoing the evidence of the photographic support. In other words, they point up the advertising envelope that has become a standard, an aesthetic value on today's art scene.

In Le même en personne. Notes sur une esthétique de la désinvolture. Text Emmanuel Hermange in Paul Pouvreau, Éditions Filigranes, 2005.

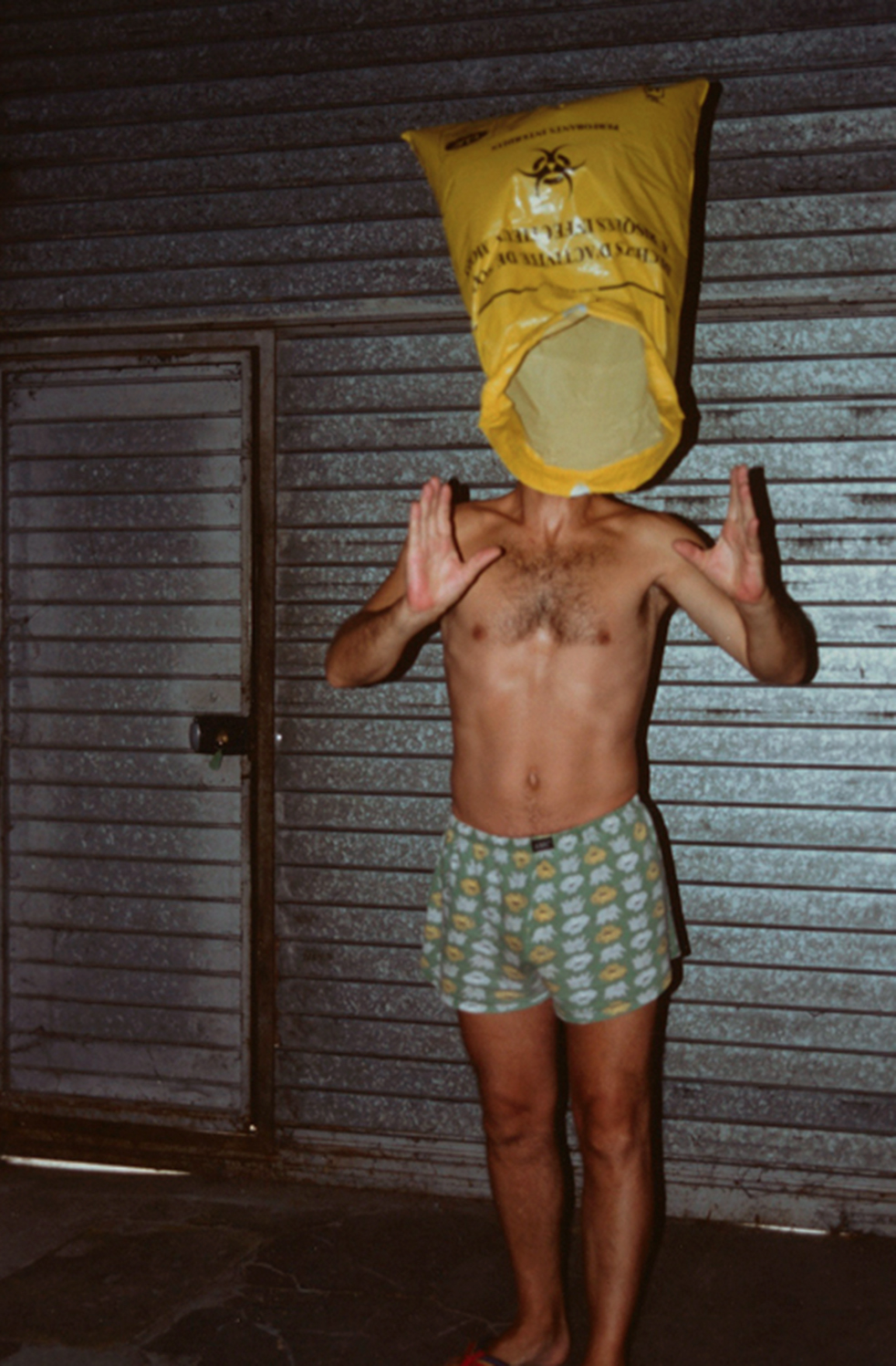

Le Porte-bouteille, 1998, 140 x 105 cm

Le magazine des jours

Solo show, Centre Photographique d’Île de France, 2019

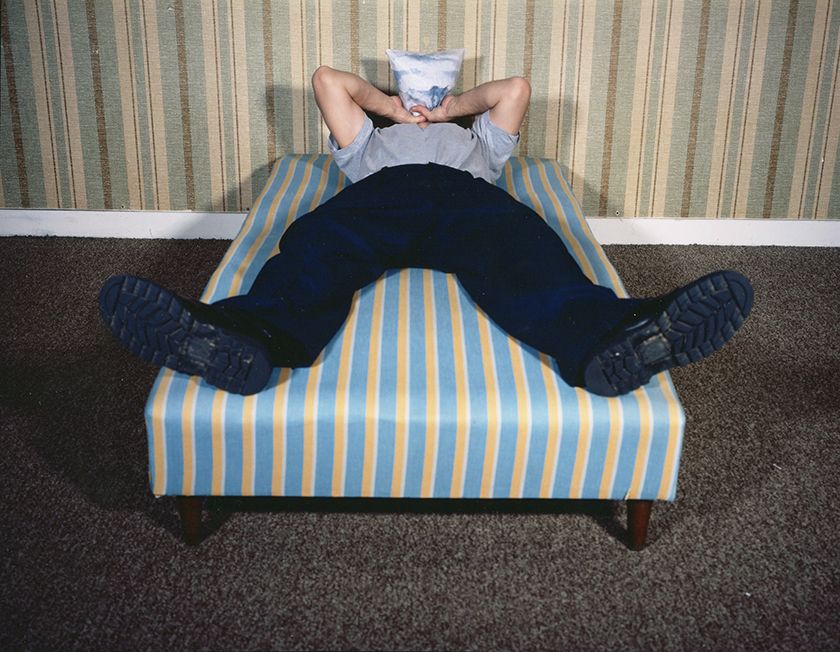

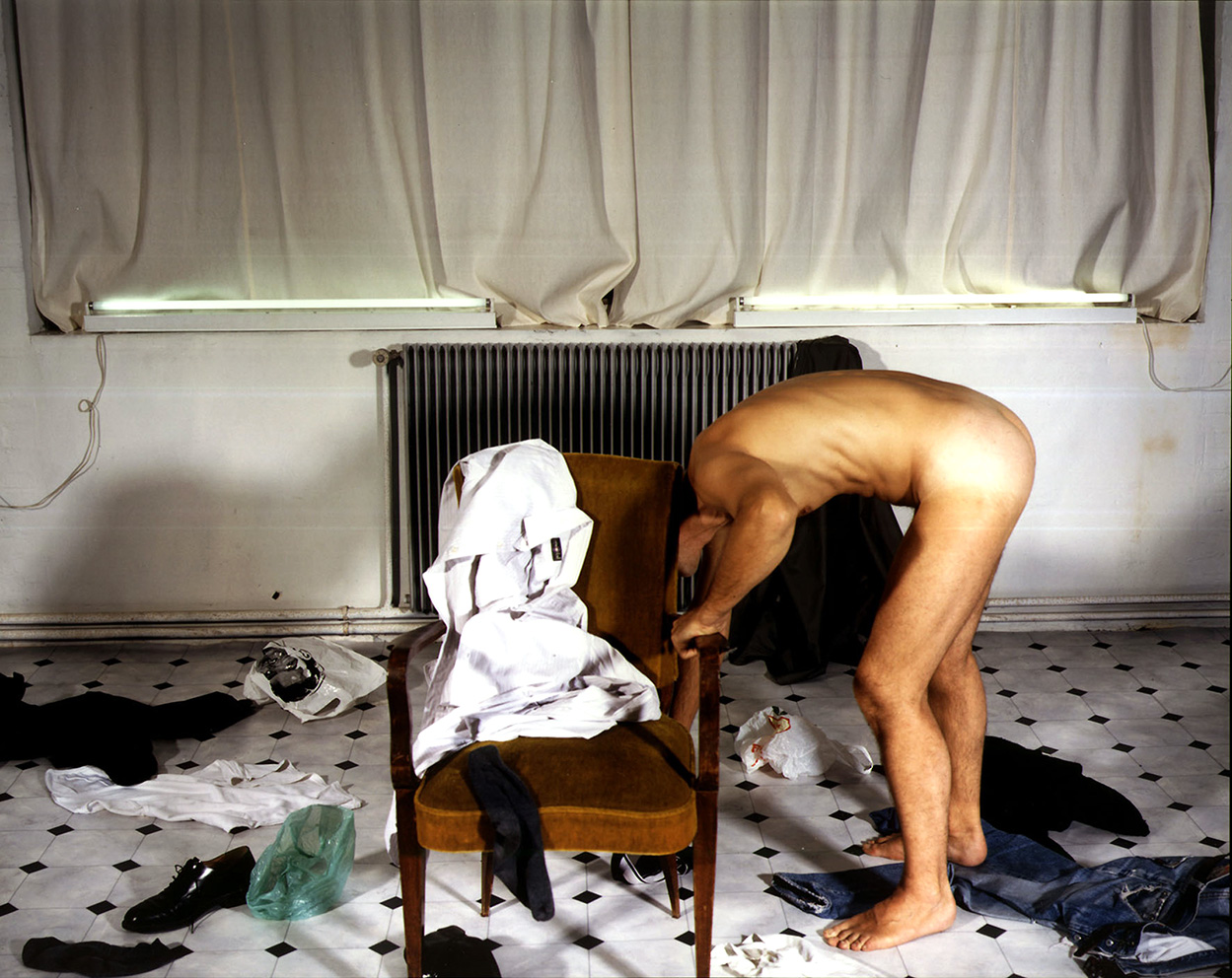

Sans titre, 1999, 90 x 130 cm

La tête dans les étoiles, 1997, 125 x 85 cm

Activités, 2002, 120 x 85 cm

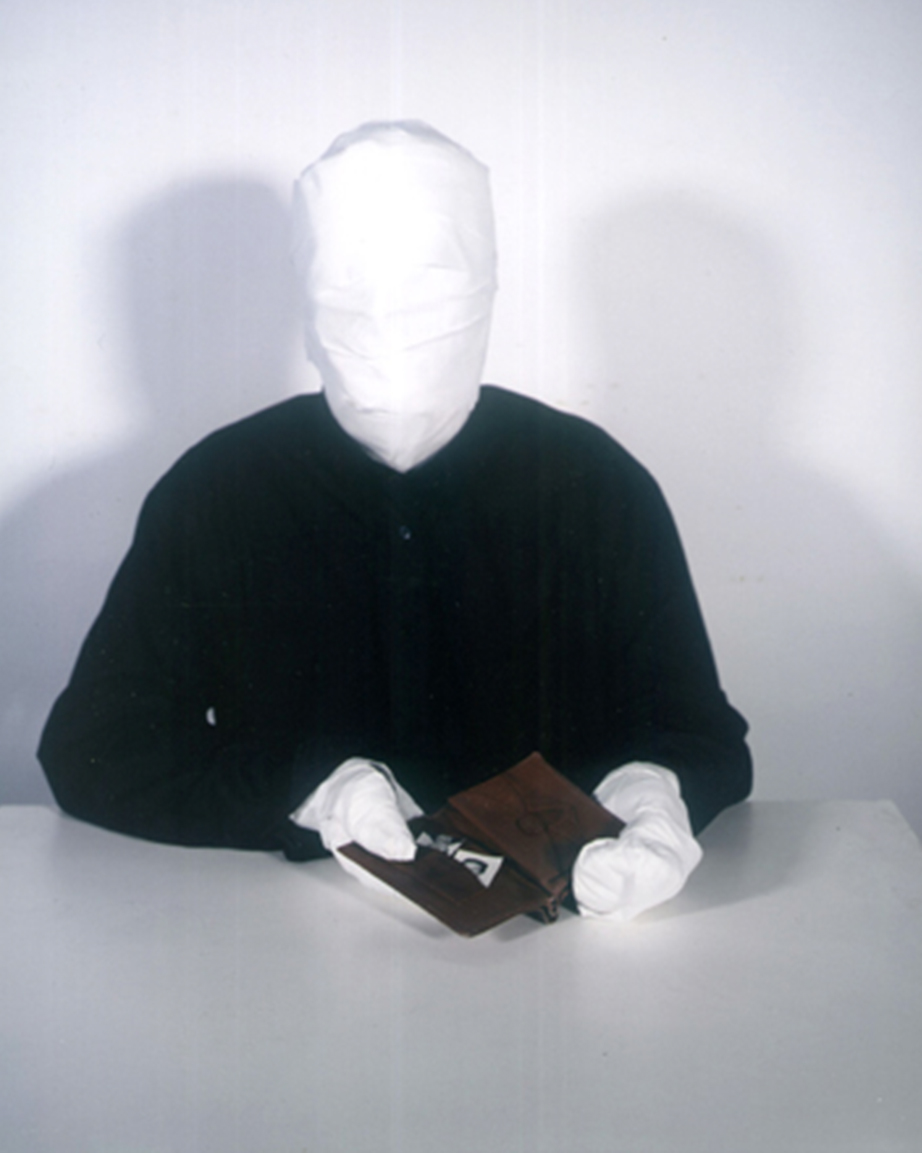

L'homme invisible, 1998, 41 x 34 cm

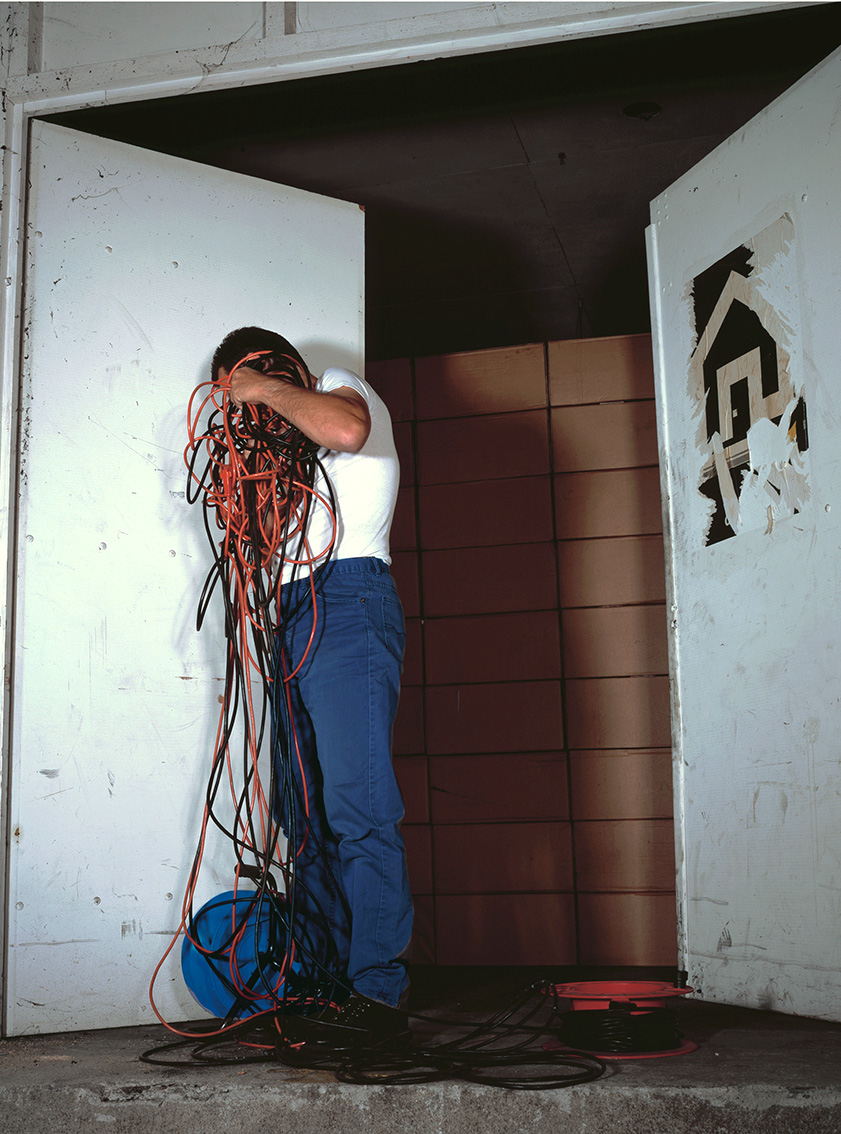

Les fils, 1999, 140 x 104 cm

L’enseigne, 1999, 140 x 95 cm

La télé, 1999, 116 x 146 cm

Le pantin, 2003, 120 x 102 cm, collection particulière

L’entreprise, 1997, 115 x 155 cm, collection particulière

La coupe, 1997, 115 x 155 cm, collection Frac Basse-Normandie

Le navigator, 1997, 115 x 155 cm, collection particulière

Le doute, 1997, 120x155 cm, collection particulière

Colonie, 2018, 80 x 120 cm

Souffler n'est pas jouer, 1998, 115 x 155 cm

Headache, 1997, 115 x 145 cm

Le modèle, 2001, 140 x 104 cm

L’opération, 2000, 95 x 145 cm, collection Frac-Artothèque Nouvelle-Aquitaine

Coup de vent, 1998, 114 x 155 cm

Camouflage, 2002, 85 x 125 cm

The dream, 2002, 105 x 150 cm

Le guet, 2002, 120 x 150 cm

Le garage, 2002, 120 x 140 cm

Eve, 2002, diptyque 2 X 120 x 82 cm

Beau jeu, 2000, 80 x 120 cm

Le cadeau (Mirande), 2008, 93 x 133 cm

Coup de point, 2002, 100 x 135 cm